In 1877 the American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) completed notoriety when he exhibited his contemporary perspectives of the river Thames on the Grosvenor Gallery in London. He gave his artwork musical titles: Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket (1875) and Nocturne in Blue and Gold – Outdated Battersea Bridge (circa 1872-5).

The view of Battersea Bridge comprises Chelsea Church and the then newly built Albert Bridge. The lighting fixtures of Cremorne Excitement Gardens twinkle within the distance, whilst fireworks explode within the faded sky above.

The portray is outstanding for its intense, mild blue tonality suggestive of night, the time of day every so often referred to as “the blue hour”. Portray from reminiscence, Whistler thinned his paint with copal (a tree resin), turpentine and linseed oil. This created what he referred to as a “sauce”, which he carried out in skinny, clear layers, wiping it away till he used to be happy. He left spaces of the darkish preparatory layer unpainted to create the appearance of the bridge. Impressed through Eastern woodblock prints, he exaggerated its top.

This newsletter is a part of Rethinking the Classics. The tales on this collection be offering insightful new techniques to consider and interpret vintage books, movies and works of art. That is the canon – with a twist.

All this used to be misplaced at the critics, alternatively. The creator Oscar Wilde reviewed the exhibition and wrote that the Battersea Bridge Nocturne used to be “worth looking at for about as long as one looks at a real rocket, that is, for somewhat less than a quarter of a minute”.

A couple of years previous Whistler had exhibited any other view of the Thames, Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Chelsea (1871), on the Dudley Gallery in London. The critic for The Instances summed up Whistler’s goal, watching that the portray used to be:

So intently similar to tune that the colors of the only would possibly and must be used, just like the ordered sounds of the opposite; that portray must now not goal at expressing dramatic feelings, depicting incidents of historical past or recording info of nature, however must be content material with moulding our moods and stirring our imaginations, through delicate mixtures of color.

Association in Grey: Portrait of the Painter through Whistler (1872).

Detroit Institute of Arts

Whistler’s artwork have been first in comparison to tune as early as 1863 when the French critic Paul Manz described his haunting portrait, The White Lady (1872), as a “symphony in white”. Whistler followed the name retrospectively, growing a sequence of 3 aesthetic temper artwork or “symphonies”, that includes younger ladies in flowing white clothes.

Press and public alike have been confused through the artist’s insistence that his artwork lacked any particular narrative or ethical message.

When he witnessed the abstraction of Whistler’s newest Nocturnes on the Grosvenor Gallery, the main English artwork critic John Ruskin printed a venomous evaluation. “I have seen, and heard much of Cockney impudence before now,” he wrote, “but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask 200 guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

Whistler’s retort

Whistler sued Ruskin for libel and used the following two-day trial to protect his perspectives on artwork. He referred to his artwork all over complaints in musical phrases, as “arrangements”, “symphonies” or “nocturnes”. When requested what the Battersea Bridge portray used to be meant to constitute, he responded:

I didn’t intend it to be a ‘correct’ portrait of the bridge. It’s only a moonlight scene … As to what the image represents, that is dependent upon who seems at it. To a couple individuals it should constitute all this is meant; to others it should constitute not anything.

Whistler gained the court docket case, however used to be awarded just a farthing in damages, leading to his chapter. Undaunted, the next 12 months (1878) he printed The Purple Rag, wherein he articulated his aesthetic idea:

Artwork must be unbiased of all clap-trap – must stand by myself, and enchantment to the creative sense of eye or ear, with out confounding this with feelings solely international to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like. These types of don’t have any roughly worry with it, and this is the reason I insist on calling my works “arrangements” and “harmonies”.

On the lookout for one thing excellent? Reduce in the course of the noise with a sparsely curated choice of the most recent releases, are living occasions and exhibitions, immediately for your inbox each fortnight, on Fridays. Enroll right here.

In 1885 he delivered his, now well-known, 10 o’clock Lecture. In it reiterated his aesthetic idea. “Nature,” he wrote, “contains the elements, in colour and form, of all pictures, as the keyboard contains the notes of all music”. He steered artists to not reproduction nature slavishly, as Ruskin had beneficial, however to means it extra like a musician, looking forward to that second when:

The night mist garments the riverside with poetry, as with a veil, and the deficient structures lose themselves within the dim sky, and the tall chimneys turn out to be campanili and the warehouses are palaces within the night time, and the entire town hangs within the heavens, and fairy-land is ahead of us.

It’s then, he argued, that nature “sings her exquisite song to the artist alone”.

Past the canon

As a part of the Rethinking the Classics collection, we’re asking our professionals to suggest a ebook or paintings that tackles identical topics to the canonical paintings in query, however isn’t (but) regarded as a vintage itself. Here’s Frances Fowles’ advice:

Whistler used to be now not the one artist of this era to view his artwork because the similar of tune. His paintings expected symbolism, a literary and inventive motion that confounded naturalistic illustration in favour of extra summary considerations, such because the connections between phrases, colors and musical notes.

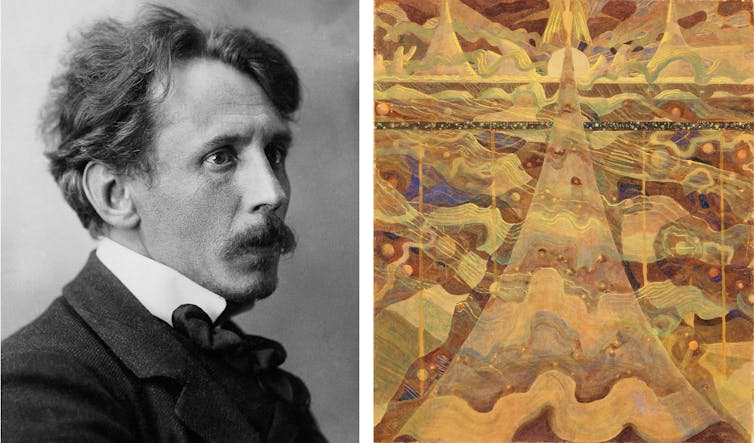

Mikalojus Čiurlionis and his 1908 portray, Stellar Sonata.

Wiki Commons

The connection between color, rhythm and sound used to be central to the paintings of French artist Paul Signac (1863-1935), who labored in a pointillist methodology (making use of dots of color), and assigned his artwork opus numbers and tempos. The Lithuanian painter and composer Mikalojus Čiurlionis (1875-1911), too, fused tune and color and gave his works of art musical titles.