Once I learn and learn about Walt Whitman’s poetry, I ceaselessly believe what he would’ve achieved if he had a smartphone and an Instagram account.

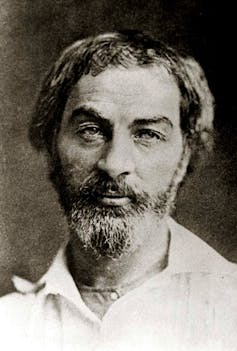

Not like lots of his contemporaries, the poet accumulated an “abundance of photographs” of himself, as Whitman student Ed Folsom issues out. And prefer many of us these days who snap and submit hundreds of selfies, Whitman, who lived right through the start of business pictures, used portraits to craft a model of the self that wasn’t essentially grounded in fact.

A type of portraits, taken through photographer Curtis Taylor, was once commissioned through Whitman within the 1870s.

In it, the poet is seated nonchalantly, with a moth or butterfly showing to have landed on his outstretched finger. In keeping with no less than two of his buddies, Philadelphia lawyer Thomas Donaldson and nurse Elizabeth Keller, this was once Whitman’s favourite {photograph}.

Regardless that he advised his buddies that the winged insect came about to land on his finger right through the shoot, it grew to become out to be a cardboard prop.

Feigned spontaneity

The scene with the butterfly displays one of the vital major subject matters of Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass,” his best-known number of poems: The universe is of course attracted to the poet.

“To me the converging objects of the world perpetually flow,” he insists in “Song of Myself.”

“I have instant conductors all over me whether I pass or stop,” Whitman provides. “They seize every object and lead it harmlessly through me.”

Whitman advised Horace Traubel, the poet’s shut buddy and earliest biographer, that “[y]es – that was an actual moth, the picture is substantially literal.” Likewise, he advised historian William Roscoe Thayer: “I’ve always had the knack of attracting birds and butterflies and other wild critters.”

In fact, historians now know that the butterfly was once, in reality, a cutout, which lately is living on the Library of Congress.

The card prop utilized by Walt Whitman within the portrait.

Library of Congress

So what was once Whitman doing? Why would he lie? I will be able to’t get within his head, however I think he sought after to provoke his target audience, to make sure that the protagonist of “Leaves of Grass,” the only with “instant conductors,” was once no longer a fictional advent.

These days’s selfies ceaselessly give the influence of getting been taken at the spot. Actually, lots of them are a in moderation calculated inventive act.

Media students James E. Katz and Elizabeth Thomas Crocker have argued that almost all selfie-takers attempt for informality at the same time as they in moderation degree the pictures. In different phrases, the selfie weds the spontaneous to the intentional.

Whitman does precisely this, presenting a designed picture as though it had been a contented coincidence.

An excessive amount of me

As Whitman biographer Justin Kaplan notes, no different author on the time “was so systematically recorded or so concerned with the strategic uses of his pictures and their projective meanings for himself and the public.”

Walt Whitman in an 1854 {photograph} most probably taken through Gabriel Harrison.

Wikimedia Commons

The poet jumped on the alternative to have his picture taken. There may be, as an example, the well-known portrait of the younger, carefree poet that was once used because the frontispiece for the primary version of “Leaves of Grass.” Or the 1854 {photograph} of a bearded and unkempt Whitman most probably captured through Gabriel Harrison. Or the 1869 symbol of Whitman smiling lovingly at Peter Doyle, the poet’s intimate buddy and possible lover.

Some social scientists have argued that these days’s selfies can assist within the seek for one’s “authentic self” – working out who you might be and working out what makes you tick.

Different researchers have taken a much less rosy view of the selfie, caution that snapping too many could be a signal of low vainness and will, mockingly, result in id confusion, in particular in the event that they’re taken to hunt exterior validation.

Whitman spent his lifestyles in search of what he termed the “Me myself” or the “real Me.” Pictures equipped him some other medium, but even so poetry, to hold in this seek. However it sort of feels to have in the end failed him.

Having accumulated those photographs, he would then obsessively bite over what all of them added as much as, in the end discovering that he was once way more misplaced than discovered on this sea of portraits.

I ponder whether – to make use of these days’s parlance – Whitman “scrolled” his method right into a disaster of self-identity, beaten through the sheer choice of footage he possessed and the more than a few, contradictory selves they represented.

“I meet new Walt Whitmans every day,” he as soon as mentioned. “There are a dozen of me afloat. I don’t know which Walt Whitman I am.”