Between 1400 and 1780, an estimated 100,000 folks, most commonly girls, have been prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe. About part that quantity have been finished – killings motivated through a constellation of ideals about girls, reality, evil and magic.

However the witch hunts may just now not have had the achieve they did with out the media equipment that made them imaginable: an business of revealed manuals that taught readers tips on how to in finding and exterminate witches.

I often educate a category on philosophy and witchcraft, the place we talk about the non secular, social, financial and philosophical contexts of early trendy witch hunts in Europe and colonial The united states. I additionally educate and analysis the ethics of virtual applied sciences.

Those fields aren’t as other as they appear. The parallels between the unfold of false knowledge within the witch-hunting technology and in as of late’s on-line knowledge ecosystem are hanging – and instructive.

Start of a publishing empire

The printing press, invented round 1440, revolutionized how knowledge unfold – serving to to create the technology’s identical of a viral conspiracy concept.

Via 1486, two Dominican friars had revealed the “Malleus Maleficarum,” or “Hammer of Witches.” The e-book has 3 central claims that got here to dominate the witch hunts.

A 1669 version of ‘Malleus Maleficarum.’

Wellcome Assortment/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

First, it describes girls as morally susceptible and subsequently much more likely to be witches. 2nd, it tightly hyperlinks witchcraft with sexuality. The authors declare that girls are sexually insatiable – a part of what leads them to witchcraft. 3rd, witchcraft comes to a pact with the satan, who tempts would-be witches via pleasures akin to orgies and sexual favors. After setting up those “facts,” the authors conclude with directions for interrogating, torturing and punishing witches.

The e-book used to be a success. It had greater than two dozen editions and used to be translated into a couple of languages. Whilst “Malleus Maleficarum” used to be now not the one textual content of its sort, its affect used to be huge.

Previous to 1500, witch hunts in Europe have been uncommon. However after the “Malleus Maleficarum,” they picked up steam. Certainly, new printings of the e-book correlate with surges in witch-hunting in Central Europe. The e-book’s luck wasn’t as regards to content material; it used to be about credibility. Pope Blameless VIII had lately affirmed the life of witches and conferred authority on inquisitors to persecute them, giving the e-book additional authority.

Concepts about witches from previous texts and folklore – such because the “fact” that witches may just use spells to make penises vanish – have been recycled and repackaged within the “Malleus Maleficarum,” which in flip served as a “source” for long run works. It used to be ceaselessly quoted in later manuals and woven into civic regulation.

The recognition and affect of the e-book helped crystallize a brand new area of experience: demonologist, a professional at the nefarious actions of witches. As demonologists repeated one some other’s spurious claims, an echo chamber of “evidence” used to be born. The id of the witch used to be thus formalized: unhealthy and decisively feminine.

Skeptics struggle again

Now not everybody purchased into the witch hysteria. As early as 1563, dissenting voices emerged – despite the fact that, significantly, maximum didn’t argue that witches weren’t actual. As a substitute, they wondered the strategies used to spot and prosecute them.

Essayist Michel de Montaigne, painted round 1578 through an unknown artist.

Conde Museum/Wikimedia Commons

Dutch doctor Johann Weyer argued that girls accused of witchcraft have been affected by melancholia – what we may now name psychological sickness – and wanted scientific remedy, now not execution. In 1580, French thinker Michel de Montaigne visited imprisoned witches and concluded they wanted “hellebore rather than hemlock”: medication quite than poison.

Those skeptics additionally recognized one thing extra insidious: the ethical duty of folks spreading the tales. In 1677, English chaplain, doctor and thinker John Webster wrote a scathing critique, claiming that the majority demonologists’ texts have been easy reproduction and paste jobs the place the authors repeated one some other’s lies. The demonologists presented no authentic research, no proof and no witnesses – failing to fulfill the criteria of excellent scholarship.

The price of this failure used to be huge. As Montaigne wrote, “The witches of my neighborhood are in mortal danger every time some new author comes along and attests to the reality of their visions.”

Demonologists benefited from the social and political standing related to the recognition in their books. The monetary get advantages used to be, for essentially the most phase, loved through the printers and booksellers – what as of late we confer with as publishers.

Witch hunts petered out during the 1700s throughout Europe. Doubt in regards to the requirements of proof, and larger consciousness that accused “witches” could have been affected by myth, have been elements after all of the persecution. The skeptics’ voices have been heard.

Psychology of viral lies

Early trendy skeptics understood one thing we’re nonetheless grappling with as of late: Positive individuals are extra prone to believing peculiar claims. They recognized “melancholics,” folks predisposed to anxiousness and fantastical pondering, as specifically prone.

Nicolas Malebranche, a Seventeenth-century French thinker, believed that our imaginations have huge energy to persuade us of items that aren’t true – particularly worry of invisible, malevolent forces. He famous that “extravagant tales of witchcraft are taken as authentic histories,” expanding folks’s credulity. The extra tales, and the extra they have been advised, the higher the affect at the creativeness. The repetition served as false affirmation.

“If they were to cease punishing (women accused of witchcraft) and treat them as mad people,” Malebranche wrote, “in a little while they would no longer be sorcerers.”

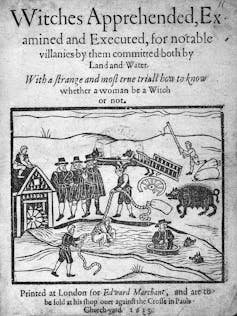

The identify web page of a treatise on witchcraft from 1613.

Wellcome Assortment/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

As of late’s researchers have recognized identical patterns in how incorrect information and disinformation – false knowledge supposed to confuse or manipulate folks – spreads on-line. We’re much more likely to consider tales that really feel acquainted, tales that connect with content material we’ve up to now observed. Likes, stocks and retweets turns into proxies for reality. Emotional content material designed to surprise or outrage spreads a long way and speedy.

Social media channels are specifically fertile flooring. Firms’ algorithms are designed to maximise engagement, so a publish that receives likes, stocks and feedback shall be proven to extra folks. The extra audience, the upper the chance of extra engagement, and so forth – making a cycle of affirmation bias.

Pace of a keystroke

Early trendy skeptics reserved their most harsh complaint now not for individuals who believed in witches however for individuals who unfold the tales. But they have been interestingly silent at the final arbiters and monetary beneficiaries of what were given revealed and circulated: the publishers.

The witch hunts be offering a sobering reminder that myth and incorrect information are ordinary options of human society, particularly all through instances of technological trade and social upheaval. As we navigate our personal knowledge revolution, the ones early skeptics’ questions stay pressing: Who bears duty when false knowledge ends up in actual hurt? How will we offer protection to essentially the most prone from exploitation through those that take advantage of confusion and worry?

In an age when any individual is usually a writer, and indulgent stories unfold on the velocity of a keystroke, working out how earlier societies handled identical demanding situations isn’t simply instructional – it’s crucial.