The picture is stark and surprising. A decapitated head, her eyes open, her mouth agape in a silent scream, her hair a nest of still-hissing snakes. Blood pours out from her severed neck. She isn’t relatively alive, however she isn’t but lifeless both.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Head of Medusa (1597) stays one of the vital memorable photographs of Italian baroque artwork. Now in Florence’s Uffizi gallery, it tells the tale of the “monster” Medusa, the snake-headed Gorgon whose stare turns whoever dares have a look at her to stone.

In classical mythology, it’s the speeding younger hero Perseus who manages to slay the monster, heading off her fatal gaze by way of the usage of his protect as a reflect and beheading her in a single fell swoop. Caravaggio’s Head of Medusa portrays the instant simply after the beheading, Medusa’s eyes huge in anguish, her brows furrowed, nonetheless apparently in disbelief at her dying.

What’s suave in regards to the portray is that Medusa’s gaze is forged somewhat downwards, in order that she does now not glance without delay on the viewer and switch us to stone. Moderately, we’re the ones given the facility to have a look at her.

Intriguingly, Caravaggio’s paintings could also be reputed to be a self-portrait. On this means, Caravaggio – just like the viewer – manages to flee the Gorgon’s deadly gaze, and the portray itself turns into a meditation now not most effective on violence but additionally at the artist’s energy of immortality – his options frozen in time perpetually.

This newsletter is a part of Rethinking the Classics. The tales on this collection be offering insightful new tactics to consider and interpret vintage books and works of art. That is the canon – with a twist.

In a feat of technical prowess, Caravaggio painted Medusa onto a real protect, the very object of her personal death. Its convex floor signifies that, as you stroll round it, you spot other angles. Relying for your point of view, some parts are hidden whilst others are printed.

This selection echoes the layers of the Medusa tale. This fictional femicide tells greater than the easy tale of guy kills monster and saves the day.

Because the Roman poet Ovid tells it in guide 4 of his epic poem Metamorphoses (the place it’s, in reality, Perseus who will get to inform her tale, the person talking for the girl as he brandishes her impotent head round for all to look), Medusa was once reworked right into a monster as a punishment. Her crime? That she was once raped by way of the ocean god Poseidon. The girl punished for her personal rape, deemed monstrous, whilst the male culprit will get off scot-free. It’s the traditional similar of “she was asking for it”.

Unmasking Medusa

It was once Medusa’s personal tale – the face of the girl at the back of the monster’s masks – that I aimed to re-collect and re-frame in my dance piece Most probably Terpsichore? (Fragments), which I made for the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 2018.

This efficiency paintings bureaucracy a part of my wider analysis investigating the novel energy and attainable of dance within the museum as an cutting edge means of studying, viewing and working out historical historical past and tradition another way. It’s one thing I time period “radical archaeology”.

The creator’s dance efficiency.

Medusa has been appropriated by way of each psychoanalysis and feminism (see, for instance, French second-wave feminist Helene Cixous’ robust 1975 essay The Giggle of the Medusa). She is, as classics pupil Helen Lovatt places it, “a pin-up for female objectification”. Medusa is monstrous and petrifying, but additionally raped and objectified.

Her tale continues to resonate in our post-MeToo instances. In her guide Girls and Energy (2017), classicist Mary Beard issues to Medusa’s decapitated head as a defining symbol of the novel separation – actual, cultural and imaginary – between girls and tool in western historical past.

Beard brings the picture up-to-the-minute with an exploration of ways it’s nonetheless used nowadays to split girls from political energy. She cites, as one instance, the nastier products on be offering to supporters of Donald Trump all the way through the United States election marketing campaign of 2016. Mugs and T-shirts bore the picture of Trump as Perseus brandishing the dripping head of Hillary Clinton as Medusa.

Beard additionally issues to the instance when Dilma Rousseff, a former president of Brazil, opened a big Caravaggio display in São Paolo. She was once requested to face in entrance of the Medusa at a photograph alternative the baying press may just merely now not face up to.

Curiously, Medusa’s head was once itself popularly represented in antiquity on an object referred to as a gorgoneion – an amulet designed to avert evil. It was once a formidable symbol, one in all coverage, in a position to chase away threat.

I imagine it’s time to reclaim this symbolism – to look Medusa as a logo of feminine empowerment, of legit rage and resistance. So take every other have a look at Medusa – dare to appear her within the eyes and even perhaps, like Caravaggio, let her face take by yourself options.

Past the canon

Pan Macmillan

As a part of the Rethinking the Classics collection, we’re asking our professionals to suggest a guide or paintings that tackles identical subject matters to the canonical paintings in query, however isn’t (but) regarded as a vintage itself. This is Marie-Louise Crawley’s recommendation:

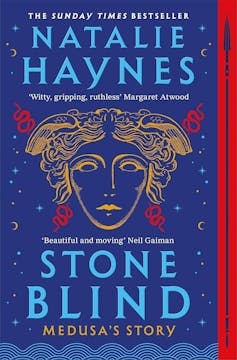

Readers short of to grasp extra about Medusa may experience Natalie Haynes’ novel Stone Blind (2022).

A classicist and comic, Haynes can frequently be discovered “standing up” for the classics as a part of her full of life BBC Radio 4 collection of the similar title, right here gives an lively feminist retelling of the Medusa and Perseus tale.

Pointing to the male violence on the centre of the tale, Haynes’ novel bitingly flips the query of who’s the hero and who’s the actual monster.

Searching for one thing just right? Reduce throughout the noise with a sparsely curated choice of the newest releases, reside occasions and exhibitions, immediately in your inbox each fortnight, on Fridays. Enroll right here.

This newsletter options references to books which have been incorporated for editorial causes, and might include hyperlinks to bookstore.org. Should you click on on one of the vital hyperlinks and cross on to shop for one thing from bookstore.org The Dialog UK might earn a fee.