Consider participating in a televised festival the place successful the automobile is the prize. There are 3 closed doorways in entrance of you: at the back of one is a automotive, and at the back of the opposite are two goats. To win the automobile, you need to wager which door it’s at the back of. And it might be any of the ones 3.

The host asks you to select one. He does it. After that, he opens one of the most unchosen doorways and divulges the goat. Then comes the an important query: do you need to stay your selection or transfer to every other one?

Most of the people suppose it’s not relevant: first of all, with 3 doorways, the chance of hiding a automotive was once 33–33–33; Now that there are two, we’re left with 50–50. However it isn’t like that.

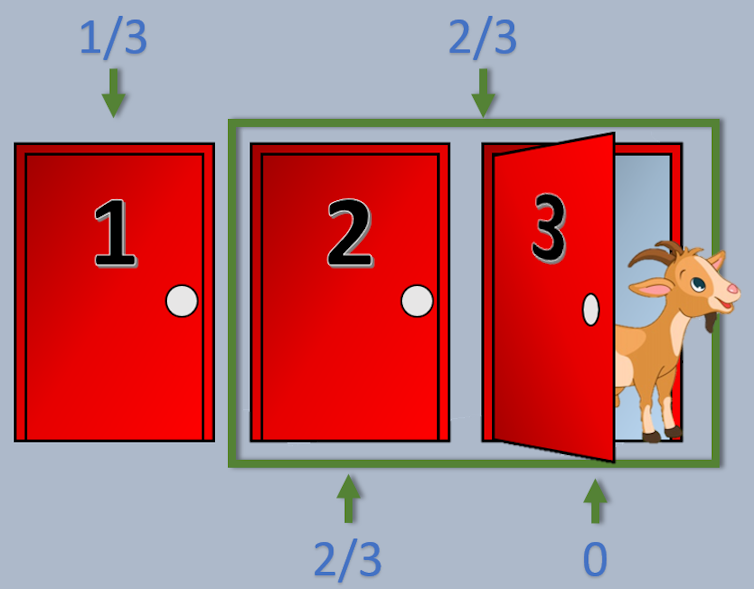

The auto has a 1/3 probability of being at the back of the door selected via the participant. The opposite two doorways have chance 2/3. Joaquin Cordova / Wikimedia Commons., CC BI Statistical illusions

This little recreation is known as the Monty Corridor downside, after the host of the American tv display Let’s Make a Deal. The issue was once posed and solved via mathematician Steve Selwyn in 1975. And it has develop into one of the well-known puzzles in statistics, as it demanding situations our instinct in a nearly ugly method.

It’s once in a while described as a statistical phantasm, even in specialist publications, on account of the gap between what we really feel must occur and what if truth be told occurs.

When the host opens the door, the possibilities for the 2 units don’t alternate, however the possibilities shift to 0 for the open door; and a couple of/3 for closed doorways (2). Joaquin Cordova / Wikimedia Commons., CC BI

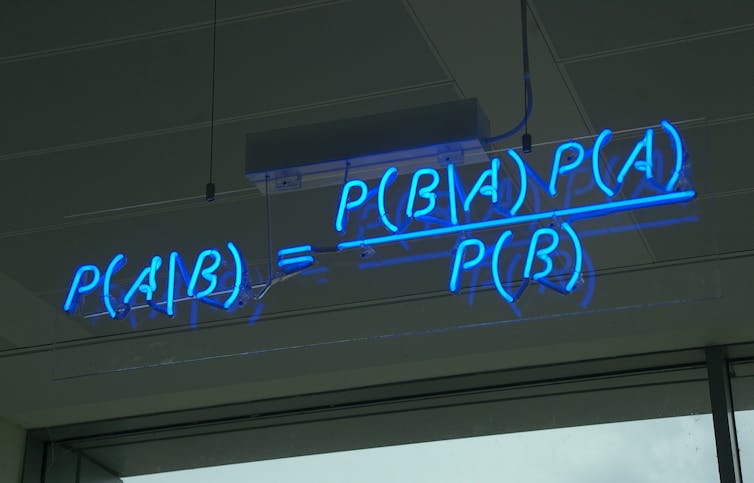

What is attention-grabbing is that at the back of this reputedly trivial determination is the truth that once we get new knowledge – although it is going to appear inappropriate – our possibilities alternate, even though we do not at all times understand how to replace them as it should be. We input the area of arithmetic, conditional chance and Bayes theorem, the place the whole lot turns into much less intuitive.

Alternatively, we will give an explanation for them with out the will for all this: common sense, proportionality and not unusual sense are sufficient to know why the presenter’s selection has obviously tipped the steadiness, and one of the most doorways guarantees greater than the others with regards to hiding the automobile.

Commentary of Bayes theorem. Mattbuck / Wikimedia Commons., CC BI Rationalization

We suppose that the contestant selected door A, even if the reasoning could be precisely the similar if he selected B or C.

If the contestant has selected door A, then it’s the host’s flip who can open door B or C, at all times with the one situation that the automobile isn’t proven, as a way to handle the enigma of its location, which is the important thing to the sport.

Assume you opened B, opening C would result in precisely the similar level. Thus there are two choices since B is off:

If the automobile is in A, it would additionally open B or C (each have a goat). Due to this fact, the chance that B opens isn’t 100%, however 50% shared via C.

If the automobile is in C, then door B is the one one that may be opened. If that’s the case, the chance that B will open is 100%. Two times up to sooner than.

This signifies that the truth that the presenter opened B is extra appropriate with the state of affairs “the car was in C” than with the state of affairs “the car was in A”.

Then again

We opposite the reasoning and suppose relating to the competitor, who’s the person who must make the verdict. Gazing that the presenter opened B, and because that motion is much more likely when the automobile is in C than when it’s in A, then it turns into much more likely for him that the automobile is in C than in A.

Due to this fact, if the automobile is much more likely to be in C, then converting to C will increase the chance of successful, for the reason that presenter’s habits unearths knowledge that favors that state of affairs greater than others.

To what extent? Bearing in mind that one is double the opposite (from 50% to 100%) and that there are not more choices, to finally end up with 100% because the sum of each we’re left with a distribution of 33%-66% for choices A and C, respectively.

Instinct can fail

Within the supervisor’s motivation, when opening door B, the truth that the automobile is at the back of door C has extra weight than at the back of door A. And, subsequently, it’s much more likely to be at the back of that door. This is why why, if the contestant adjustments the selection, the possibilities of successful are upper.

This clarification applies if the contestant selected A. For the opposite two choices, the means is similar: if he chooses B, A is exchanged with B. If he chooses C, A is exchanged with C.

In any case, the Monty Corridor downside reminds us that instinct can fail, even in easy scenarios. Appropriately updating knowledge does not simply alternate the end result: it adjustments our working out of ways randomness actually works.

And accepting that concept, even though it calls into query what “seems logical” to us, is an crucial a part of higher considering.