As he paced throughout a degree at an army base in Quantico, Virginia, on Sept. 30, 2025, Secretary of Protection Pete Hegseth advised the loads of U.S. generals and admirals he had summoned from world wide that he aimed to reshape the army’s tradition.

Ten new directives, he stated, would strip away what he referred to as “woke garbage” and repair what he termed a “warrior ethos.”

The word “warrior ethos” – a mixture of combativeness, toughness and dominance – has turn into central to Hegseth’s political identification. In his 2024 guide “The War on Warriors,” he insisted that the inclusion of ladies in struggle roles had tired that ethos, leaving the U.S. army much less deadly.

In his deal with, Hegseth defined what he sees because the qualities and virtues the American soldier – and particularly senior officials – must include.

On bodily health and look, he used to be blunt: “It’s completely unacceptable to see fat generals and admirals in the halls of the Pentagon and leading commands around the country and the world.”

He then became from frame form to grooming: “No more beardos,” Hegseth declared. “The era of rampant and ridiculous shaving profiles is done.”

As a historian of George Washington, I will say that the commander in leader of the Continental Military, the country’s first army chief, would have agreed with a few of Secretary Hegseth’s directives – however only a few.

Washington’s general imaginative and prescient of an army chief may just now not be farther from Hegseth’s imaginative and prescient of the cruel warrior.

U.S. Secretary of Protection Pete Hegseth speaks to senior army leaders at Marine Corps Base Quantico on Sept. 30, 2025.

Andrew Harnik/Getty Photographs

280 kilos – and depended on

For starters, Washington would have discovered the fear with “fat generals” beside the point. Probably the most maximum succesful officials within the Continental Military have been famously obese.

His depended on leader of artillery, Gen. Henry Knox, weighed round 280 kilos. The French officer Marquis de Chastellux described Knox as “a man of thirty-five, very fat, but very active, and of a gay and amiable character.”

Others weren’t a ways in the back of. Chastellux additionally described Gen. William Heath as having “a noble and open countenance.” His bald head and “corpulence,” he added, gave him “a striking resemblance to Lord Granby,” the prestigious British hero of the Seven Years’ Conflict. Granby used to be admired for his braveness, generosity and devotion to his males.

Washington by no means noticed girth as disqualifying. He many times entrusted Knox with essentially the most hard assignments: designing fortifications, commanding artillery and orchestrating the mythical “noble train of artillery” that introduced cannon from Castle Ticonderoga to Boston.

When he turned into president, after the Revolution, Washington appointed Knox the primary secretary of conflict – an indication of tolerating self belief in his judgment and integrity.

Beards: Outward look displays interior self-discipline

As for beards, Washington would have shared Hegseth’s worry – even though for extraordinarily other causes.

He disliked facial hair on himself and on others, together with his infantrymen. To Washington, a beard made a person glance unkempt and slovenly, protecting the upper feelings that civility required.

Beards weren’t indicators of virility however of dysfunction. In his phrases, they made a person “unsoldierlike.” Each soldier, he insisted, will have to seem in public “as decent as his circumstances will permit.” Every used to be required to have “his beard shaved – hair combed – face washed – and cloaths put on in the best manner in his power.”

For Washington, this used to be no trivial topic. Outward look mirrored interior self-discipline. He believed {that a} well-ordered frame produced a well-ordered thoughts.

To him, neatness used to be the visual expression of self-command, the root of each different distinctive feature a soldier and chief must possess.

Because of this he equated beards and different sorts of unkemptness with “indecency.” His lifelong combat used to be in opposition to indecency in all its paperwork. “Indecency,” he as soon as wrote, used to be “utterly inconsistent with that delicacy of character, which an officer ought under every circumstance to preserve.”

Extra statesman than warrior

By way of “delicacy,” Washington supposed modesty, tact and self-awareness – the poise that set authentic leaders excluding people ruled through passions.

For him, a soldier’s first victory used to be at all times over himself.

“A man attentive to his duty,” he wrote, “feels something within him that tells him the first measure is dictated by that prudence which ought to govern all men who commits a trust to another.”

In different phrases, Washington turned into a soldier now not as a result of he used to be hotheaded or attracted to the fun of struggle, however as a result of he noticed soldiering because the perfect workout of self-discipline, persistence and composure. His “warrior ethos” used to be ethical earlier than it used to be martial.

Washington’s best army chief used to be extra statesman than warrior. He believed that army energy will have to be exercised beneath ethical constraint, inside the bounds of public duty, and at all times with a watch to retaining liberty quite than successful private glory.

In his thoughts, the military used to be now not a caste aside however an software of the republic – an enviornment through which self-command and civic distinctive feature have been examined. Later generations would name him the style of the “republican general”: a commander whose authority rested now not on bluster or bravado however on composure, prudence and reticence.

That imaginative and prescient used to be the other of the only Pete Hegseth carried out at Quantico.

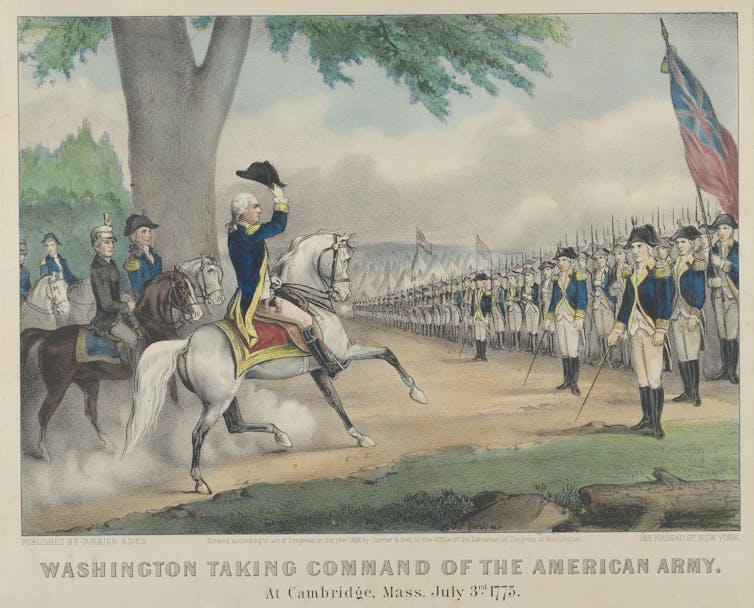

Washington officially taking command of the Continental Military on July 3, 1775, in Cambridge, Mass.

Currier and Ives symbol, picture through Heritage Artwork/Heritage Photographs by way of Getty Photographs

Self-discipline and stability, now not fury and bravery

The “warrior ethos” Hegseth celebrates – loud, performative – used to be exactly what Washington believed a soldier will have to conquer.

In March 1778, after Marquis de Lafayette deserted an unimaginable wintry weather expedition to Canada, Washington praised warning over juvenile bravado.

“Every one will applaud your prudence in renouncing a project in which you would vainly have attempted physical impossibilities,” he wrote from the snows of Valley Forge.

For Washington, valor used to be by no means the similar as recklessness. Luck, he believed, trusted foresight, now not fury, and in no way bravado.

The primary commander in leader cared little for waistlines or whiskers, finally; what involved him used to be self-discipline of the thoughts. What counted used to be now not the reduce of a person’s determine however the stability of his judgment.

Washington’s personal “warrior ethos” used to be grounded in decency, temperance and the capability to behave with braveness with out surrendering to rage. That best constructed a military – and in time, a republic.