“Just Because I am a Librarian doesn’t mean I have to dress like one.”

With this breezy pronouncement, Belle da Costa Greene handily differentiated herself from maximum librarians.

She stood out for different causes, too.

Within the early twentieth century – a time when males held maximum positions of authority – Greene used to be a celebrated e-book agent, a curator and the primary director of the Morgan Library. She additionally earned US$10,000 a yr, about $280,000 lately, whilst different librarians had been making kind of $400.

She used to be additionally a Black girl who handed as white.

Born in 1879, Belle used to be the daughter of 2 light-skinned Black American citizens, Genevieve Fleet and Richard T. Greener, the primary Black guy to graduate from Harvard. When the 2 separated in 1897, Fleet modified the circle of relatives’s ultimate identify to Greene and, along side her 5 youngsters, crossed the colour line. Belle Marion Greener changed into Belle da Costa Greene – the “da Costa” a refined declare to her Portuguese ancestry.

Probably the most 9 recognized portraits of Belle da Costa Greene that photographer Clarence H. White made in 1911.

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard College Heart for Italian Renaissance Research

When banking multi-millionaire J.P. Morgan sought a librarian in 1905, his nephew Junius Morgan really useful Greene, who were considered one of his co-workers on the Princeton Library.

Henceforth, Greene’s existence didn’t simply kick into the next tools. It used to be supercharged. She changed into a full of life fixture at social gatherings amongst The united states’s wealthiest households. Her global encompassed Gilded Age mansions, nation retreats, uncommon e-book enclaves, public sale properties, museums and artwork galleries. Daring, vivacious and glamorous, the keenly clever Greene attracted consideration anywhere she went.

I discovered myself interested in the worlds Greene entered and the folks she described in her energetic letters to her lover, artwork pupil Bernard Berenson. In 2024, I revealed a e-book, “Becoming Belle Da Costa Greene,” which explores her voice, her self-invention, her love of artwork and literature, and her path-breaking paintings as a librarian.

But I’m regularly requested whether or not Greene mentions her passing as white in her writings. She didn’t. Greene used to be considered one of masses of hundreds of light-skinned Black American citizens who handed as white within the Jim Crow technology. Whilst hypothesis about Greene’s background circulated in her lifetime, not anything used to be showed till historian Jean Strouse printed the identities of Greene’s folks in her 1999 biography, “Morgan: American Financier.” Till that time, most effective Greene’s mom and siblings knew the tale in their Black heritage.

“Passing” can regularly elevate extra questions than solutions. However Greene didn’t in large part outline herself via one class, equivalent to her racial id. As a substitute, she built a self during the issues she cherished.

‘I love this life – don’t you?’

For my part, any attention of Greene’s attitudes towards her personal race will have to stay an open query. And uncertainty may also be said – even embraced – with judgments suspended.

The Morgan Library & Museum these days has an exhibition on Greene that can run till Would possibly 4, 2025 – one who’s already generated debates about Greene and the importance of her passing.

One segment of the exhibition, “Questioning the Color Line,” contains novels on passing, art work equivalent to Archibald J. Motley Jr.’s “The Octoroon Girl,” pictures of Greene, and clips from Oscar Micheaux’s 1932 movie “Veiled Aristocrats” and John M. Stahl’s 1934 movie “Imitation of Life,” which painting painful scenes between white-passing characters and their members of the family.

None of those gadgets clarifies Greene’s explicit dating to passing. As a substitute, they position the librarian inside of melodramatic and standard representations about passing that pressure self-division and angst.

We don’t know – possibly we will be able to by no means know – whether or not Greene had identical moments of self-doubt.

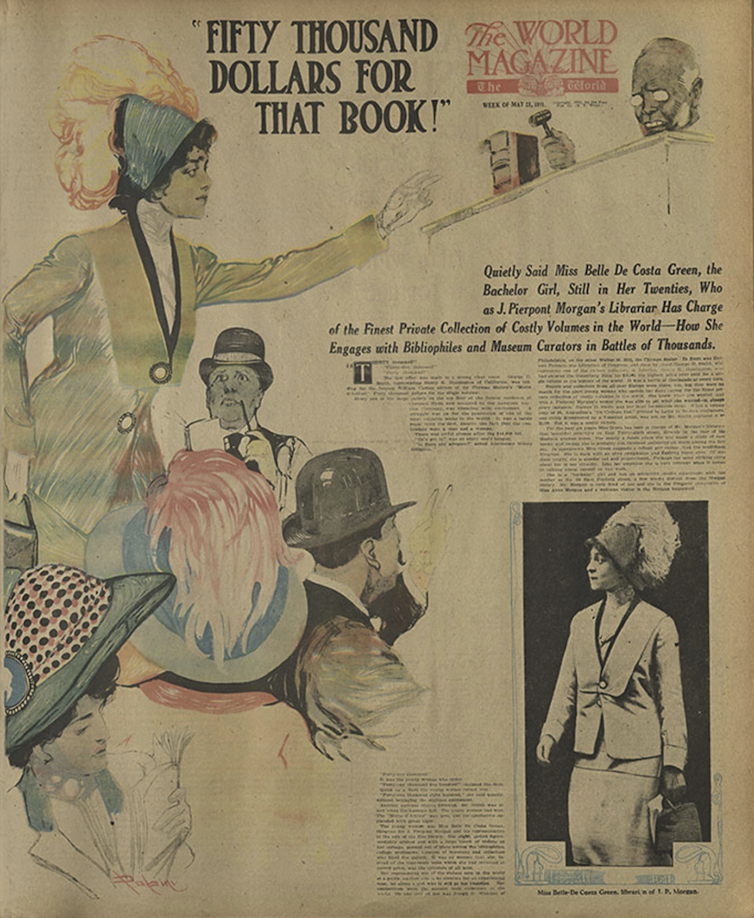

Greene often won sparkling press protection.

The Morgan Library & Museum

But some critics have concluded as a lot. In his assessment of the exhibition for The New Yorker, critic Hilton Als laments what Greene’s passing had price her. He describes her as a “girl who loved power,” a girl who “became a member of another race – not Black or white but alternately grandiose and self-despising.”

There’s a large number of walk in the park in this kind of pronouncement – and scant proof furnished to beef up such declarations.

New York Occasions columnist John McWhorter takes factor with Als’s depiction of the librarian’s passing in a Jan. 23, 2025, article.

Mentioning passages from her letters by which Greene excitedly describes studying the Arabic folktales “The Thousand and One Nights” and seeing exhibitions of contemporary artwork, McWhorter asks readers to rethink this “witty, puckish soul who savored books and art” and “had an active social life.”

What if Greene gave her race little concept, McWhorter wonders. What if she merely noticed the perception of race and racial categorization as “a fiction” and as an alternative lived her existence to its fullest? After all, her gentle pores and skin afforded her the chance that different Black other people of her technology didn’t have. However does that essentially imply that she used to be self-loathing or conflicted?

“[W]e are all wearing trousers and I love them,” Greene writes in a single letter to Berenson, including, “The Library grows more wonderful every day and I am terribly happy in my work here … I love this life – don’t you?”

Greene’s energy captivated Berenson, who as soon as described the librarian as “incredibly and miraculously responsive.”

The gourmet used to be now not the one fresh who admired Greene’s effervescence. In “The Living Present,” an account of the actions of girls sooner than and after Global Battle II, Greene’s pal Gertrude Atherton paid tribute to Greene, a “girl so fond of society, so fashionable in dress and appointments” that she may galvanize any stranger along with her “overflowing joie de vivre.”

Crafting an charisma

Seen via a extra expansive lens, Greene’s passing may also be noticed as a part of an workout in self-fashioning and self-invention.

Greene dressed to be spotted – and he or she used to be. Meta Harrsen, the librarian Greene employed in 1922, provides a unprecedented eye-witness account. At the day Greene interviewed Harrsen, “she wore a dress of dark red Italian brocade shot with silver threads, a gold braided girdle, and an emerald necklace.”

Greene understood smartly the ability of garments to mission a definite id – a extremely crafted one on this case, and one befitting a gourmet of uncommon books.

Greene poses for a Time mag portrait in 1915.

The Morgan Library & Museum

At that, she excelled. She changed into recognized for her surprising acquisition coups: her acquire of 16 uncommon editions of the works of English printer William Caxton at an public sale; her procurement of the extremely coveted Crusader’s Bible via a non-public negotiation; and her acquisition of the Spanish Apocalypse Remark, a medieval textual content written by means of a Spanish monk that Greene used to be ready to shop for at a steep bargain.

To me, a 1915 photograph captures Greene’s self assurance and charisma greater than another symbol of the librarian.

She posed in her house and wasn’t shot in comfortable focal point with a studio backdrop as different pictures have a tendency to painting her. Sitting at the arm of a giant chair upholstered in a tapestry weave, she wears an elaborate hat with a big ostrich plume, a high-necked shirt underneath a protracted, loosely belted jacket with a ruffled cuff over a protracted darkish skirt. The decor is not any much less putting: Flemish tapestries adorn the partitions in the back of her, and a liturgical vestment is draped over the bookcase. Taking a look at once on the viewer, Greene is confident and poised.

Greene’s fashionable aptitude used to be now not merely ornamental. It used to be a testomony to her colourful character and the enjoyment she took in her paintings. Fairly than pass judgement on her in line with fresh notions of racial id, I wish to wonder over her achievements and the way she changed into a type for generations of long term librarians.

Greene didn’t simply go. She surpassed – in impressive tactics.